The fiction of identity: veridiction and the contract of attention in the Netflix show Clickbait La fiction de l’identité : véridiction et contrat d’attention dans la mini-série de Netflix Clickbait

Marilia Jardim

Royal College of Art / London College of Communication, UK

The article utilises the analysis of the Netflix show Clickbait to explore cultural shifts in the standard logic of veridiction, which seem to break with the Greimasian model of veridictory modalities to welcome diverse procedures –such as faire semblant and authentication– governing the communication and perception of truth. Rather than a problem affecting only discourses, I aim to argue that the production of subjective identities, both in the physical world and mediated contexts, is also impacted by this change in our relationship with signs. By presenting a dialogue between theories concerned with traditional and emerging mechanisms related to veridiction, the article offers a reflection on the production and deployment of identity, and the blurring of lines between reality, unreality, and fiction, which produces simulacral dynamics shifting the goal of interactions from a sanction- to an attention-oriented model.

L’article présente une analyse de la série télévisée Clickbait produite par Netflix. Sur cette base, il examine les changements culturels dans la logique traditionnelle de la véridiction et leur rupture avec le modèle greimassien des modalités véridictoires, ouvrant la communication et la perception de la vérité à d’autres procédures, comme le faire semblant et l’authentification. Au-delà des discours, la production des identités subjectives, dans le monde matériel ainsi que dans les contextes médiatisés, est également affectée par ce changement dans notre relation avec les signes. En dialogue avec les théories des mécanismes traditionnels et émergents de la véridiction, l’article offre une réflexion sur la production et le déploiement de l’identité. De même, il interroge le flou des frontières entre réalité, déréalité et fiction qui, produisant les dynamiques de simulacres, transforment le but des interactions en passant d’un modèle centré sur la sanction vers un modèle régi par une logique de l’attention.

Index

Articles du même auteur parus dans les Actes Sémiotiques

Mots-clés : attention, déréalité, fiction, simulacre, véridiction

Keywords : Attention, Fiction, Simulacrum, Unreality, Veridiction

Auteurs cités : Juan ALONSO ALDAMA, Roland BARTHES, Anne BEYAERT-GESLIN, Jean-François BORDRON, Per Aage BRANDT, Jacques FONTANILLE, Algirdas J. GREIMAS, Anna Maria LORUSSO, Juri LOTMAN

Released in 2021, Clickbait tells the story of the havoc caused by the appearance of a video showing a man with a bruised face and holding a sign saying: “I abuse women. At 5 million views I die.” A fictional commentary of the contemporary context of a mediatised existence and its potential for distorting our perception and communication of truth, each episode presents a deeper dive into one of the characters implicated in the story and their role –not only in the diegesis but as the emblem of stratified, uni-dimensional social roles– which reconstruct, working backwards, the puzzle of a multilayered crime. By the end of the series, we learn this is a story of identity theft, in which the real catfisher, Dawn Reed, was a colleague of Nick Brewer’s, the man in the video: working in a clerical position, she had access to his computer, his phone and personal data, and occupied a privileged position of “confidant” when he experienced marital issues, thus gaining access to intimate details of his private life.

Rather than simply stealing the photographs of good-looking Nick, Dawn also used his authentic identity –information about his work, his sons, and difficulties with his wife– to create accounts on multiple dating websites and start various simultaneous virtual relationships. The show focuses on the interactions with Emma Beasley, who fully embraces and defends the “reality” of her romance with him; and Sarah Burton, who ends up taking her life when Dawn ends the interaction with her. The plot focuses on the abduction of real-life Nick Brewer by Sarah’s brother, Simon Burton, who is motivated to seek revenge against the man he saw in a photograph with his sister, using the bits of (authentic) information he recovered from Sarah’s diary and text messages in her phone. However, the photograph showing Nick and Sarah posed as a couple turns out to be a photomontage created by Dawn from a (real) couple photograph of Nick and his wife Sophie, and a similar collage had been created for Emma. As this photo is taken as true by Simon, and the cruel messages sent to Sarah are attributed to the person the image shows, he orchestrates a plot to locate and abduct real-life Nick, producing the video as part of his plan to expose and execute the man who, he believes, led his sister to suicide.

A fictional text, Clickbait offers a commentary on a certain shift in our semiotic attitude towards images, verbal language, and the construction and apprehension of identities between the substance of the material world –to which I will refer using the popular acronym “IRL”, “In Real Life”– and the digital substance of the informational world or life online. By exploring the line between fiction and veridiction and how the elements of both can overlap and interpenetrate one another, this TV series allows a fertile discussion on the matters of reality and unreality and how those realms are harnessed in a logic aimed at sustaining engagement. Transposing what Juri Lotman (1973) identifies as a symbolic or paradigmatic type of culture to the age of technology and algorithmic interactions, the dynamics disseminated in the diegesis of Clickbait also communicate a transformation in our relationship with truth: a certain disintegration of the traditional logic of veridiction in Greimasian (1976, 1983) terms, which, today, seems to be replaced by a model that is aimed at sustaining attention, rather than presenting truths that can be sanctioned. The analysis of selected characters and sections of the plot aims to explore the blurring of lines between reality and fiction as emblematic of the transformation in our relationship with veridiction (Alonso Aldama 2018; Ben Msila 2021; Lorusso 2021), as well as with the iconic (Barthes 1980; Beyaert-Geslin 2005; Bordron 2005) and verbal (Barthes 1984; Brandt 1992; Greimas 1976, 1983) substances, and their fictional and veridictory roles. In the dialogue between various developments of the theory, I will present a discussion of identity, interaction, and roles and their construction in the context represented in Clickbait, examining the extent to which those mechanisms extrapolate the traditional logic of veridiction, causing the emergence of new types of contracts governing interactions between different subjects and their projected existential simulacra.

1. Images, simulacra, and identity

Through its deconstructive representation of a complex case in which truth is mobile, formed from a fragile foundation of lies and decontextualised collections of impressions, Clickbait offers a representation of our current role within the mediated chaos of information. While the characters in the show are obsessed with (rapidly) discovering the truth of the facts, it is the truth of subjects’ identities that is being put into check. Each one of the episodes, a deep scrutiny of each of the main characters, is named after a thematic role –“The Sister”, “The Detective”, “The Wife”, “The Mistress”, “The Reporter”, “The Brother”, “The Son”, “The Answer”– while the show itself, named “clickbait”, is assigned a thematic trajectory as deceptive, sensationalised content, designed to attract clicks. This approach, however, reaches beyond the funnelling of attention towards the diegesis, creating dynamics in which IRL identities are also governed by a clickbait strategy.

In place of the holistic accumulation of life experiences Jacques Fontanille (2004) identifies with the construction of a soi-ipse, developing Paul Ricœur’s (1990) concept as a processual instance in constant becoming through the superposition of lived occurrences, the trajectories followed by the characters in the show reveal identities increasingly becoming a succession of monoisotopies that do not form syntagmatic chains. Each episode’s opening title represents such single-use patterns of behaviour as fragmented puzzles of the characters’ image, presented and arranged in an incoherent order and formed by pieces that don’t fit, that are not capable of “revealing” a totality. Beyond the idea of images as plastic or visual substances, the show addresses impressions as imprints of self, which Greimas and Fontanille (1991) defined as “existential simulacra” –the projections of subjects in a passional imaginary. In a radical reading of this model of transitory modal identities, it is possible to understand intersubjective relations as unfolding exclusively through the interaction of simulacra: as subjects double themselves into “an other”–the discursive simulacra constituting their imaginary– and interiorise this “other body” as an “inter-subject”, all communication occurs through images of oneself and others each interlocutor refers to (Greimas & Fontanille 1991:63).

The viral video around which the plot is organised is an emblematic example of this radical reading, as well as Juri Lotman’s definition of cultures of semantic (or symbolic) types. In such cultural spheres, the act of creation emerges as the formation of a sign, which effects a disjunction of social and biological realities formulated as a rejection of things to “aspire to the sign” (Lotman 1973:43). In the show’s diegesis, it is no longer subjects of flesh and bones confronting one another, but an ensemble of simulacra put into interaction –some “authentic” imprints of subjects, others manufactured through a bricolage of authentic impressions that are reorganised to mean something else. This logic, in turn, mirrors the opposition of material and ideal, in which the sign aligns with the ideal: the value of the sign lies precisely in the decrease of the material (expression) existing in it –nothing more than an “imprint” of the content, which is “the spirit” (Lotman 1973:49). As characters identify with images as signs (rather than mere expressions), their experience of identity is one of becoming image: in sincerely impersonating Nick, Dawn’s experience is one of being him in the interactions with Emma and Sarah; in turn, as they accept the contract of mediation in their relationship, Emma and Sarah both experience the reality of the romantic relationship with Nick, which is “evidenced”, among other things, by the photographic couple representations forged by Dawn.

This mechanism of identification affects both the euphoric and dysphoric set of interactions presented in the show. Sarah’s pain and death result entirely from a sign exchange, while Simon’s revenge is not against a material person but his images: the man in the photo, the words in text messages, and the phantom of a relationship that led his sister to take her life. The power of the sign is such that, in its creation –even when it’s fictional– it can grant status of reality to romantic relationships, as well as make Nick become an abuser: it is not only the public who accepts this simulacrum but, in the course of the case, the family and close friends are equally led to question the reality of their lives with Nick. Such reverence for images brings us back to a logic where the sign takes precedence over the material expression: our bodies, physical experiences, and knowing that is based on partaken immediate interactions can be questioned and denied in the face of the truth of images. Although Lotman associates this model with Mediaeval culture, Clickbait exposes the extent to which the logic of simulacral interactions, unfolding almost entirely through images, returns us to a symbolic cultural system. In such an organisation, the construction of identities deployed through mediated channels denounces the effort of subjects in controlling one’s image not as an “expression of self” but as a sign: to manipulate one’s image appears as an attempt to connect with a different content as if, by changing the imprint, one could change the “spirit”.

Rather than a false world, the constructions aimed at and deployed online cannot be taken to be “unreal” or “fictional” –even if they appropriate strategies of fiction and are coated with an aura of unreality. In the diegesis, a woman was led to IRL suicide, and an innocent man was abducted and tortured, shamed online and killed in the material world in the quest for bringing justice to Sarah. This blurring of the boundaries between fiction and description, invention and documentation, mixing the genres of entertainment, information, spectacle and debate into one is precisely the focus of Anna Maria Lorusso’s proposition of authenticity as a replacement for the traditional logic of veridiction. Her work explores a borderline set of discourses which use fragments of real, authentic experiences in a decontextualised or curated manner to construct the effect of truth. In such cases, she argues, the reality of those splinters of truth act as pollutants: although they are not falsities or lies, such elements of real reality come to play an erroneous argumentative role (Lorusso 2021:311).

In such dynamics, it is possible to identify a change in the standard logic of veridiction: a passage from truth, a supra-personal partaken contract; to authenticity, which conduces to projection and synchronisation but relies on experience as the parameter of discourse legitimation (Lorusso 2021). When Dawn uses authentic images of Nick and fragments of his life stories to construct her character, it is precisely the authenticity of the images and experience they show that make the Nick she gave life to a plausible, credible person. The told stories, events, and emotions were authentically experienced, felt, documented by real subjects. Even the photograph chosen by her to create the montages –a souvenir of a joyful moment shared by a couple– carries the authentic traces of mutual love, which was authentically lived by Nick and Sophie at that moment. However, when only sections of the object carry such traces of truth, it is no longer possible to sanction the totality of the manifestation: only the parts can be authenticated, leaving no possibility of forming a syntagmatic chain –only a paradigmatic collection of units that may or may not be sanctioned in separate, but never as a whole.

The term chosen by Lorusso to replace the mechanism of sanction, authentication, is an operation belonging to the algorithmic logic of computation, which marks our current model of communications and interactions in digital spaces. Thus, this passage from veridiction to verification can be almost entirely attributed to the ubiquity of mediation and the extent to which it permits instances of falsity –to appear to be what it is not. Although the idea of authenticity is also central to the debates around (human) identity, Anne Beyaert-Geslin distinguishes between authenticity and sincerity as two manifestations of the coincidence of being and appearing. Both instances constitute epistemological relations between an utterance and its producer, presupposing the introduction of an observer capable of establishing the adequation; however, while sincerity emerges from the relation between two subjects, authenticity is a relation between subject and object (Beyaert-Geslin 2005). The passage from sincerity –which can be associated with immediate contexts– to authentication when it comes to human identity (both in its biometrical sense and as a subjective phenomenon) exposes a level of objectification of subjects: to be authenticated is to be transformed into an artefact that can be authentic or “fake”; or into a digital simulacrum –the identity, fact, or image that must be verified.

Although the plot represents a story unfolding between the world of corporeal, lived experiences and the digital online world, we see that, in both spaces, the substances utilised to construct identity are not fleshly but verbal and iconic. Thus, images appear to be capable of “evidencing” one’s identity, but, vice versa, identity itself constructs and sanctions the meaning of images, irrespective of their “reality”. It is not the “that has been” each photograph communicates –Roland Barthes’ (1980) “necessarily real” referent of a photograph, the “emanation” of a thing rather than its representation– creating the effect of truth: on the contrary, as argued by Jean-François Bordron (2005), it is the reconciliation between the image and that which, through it, is made a subject. His analysis of the mechanism of collage in scientific photography shows the possibility that, through an image, a superposition of different impressions of the same thing can be assembled to communicate the simultaneity of realities that could not be apprehended otherwise.

Such arguments are pertinent, in the show’s context, both to the authentic images and to the manufactured ones. As the case in Clickbait unfolds, we are presented with many sequences of Sophie looking at her family photographs in conflict, searching for authentication of what she believes to be “the real Nick” –a set of impressions in direct, binary confrontation with another simulacrum, created by Simon, in which Nick is as an abuser and killer. As this second simulacrum of Nick is disseminated, multiplied, and validated by the public opinion, Sophie’s engagement with her family photos changes: from reminiscence through rejection, we see scenes of Sophie tearing down the photographs and destroying her own laptop. By the end of the show, however, as Nick’s innocence is proved, restoring a complementarity between his public and private simulacra, Sophie’s reinsertion of Nick as part of her true reality is represented in the act of repositioning the photographs in their original places, as if what the images show is once again reconciled with what the photos “make a subject”. It is only through the destruction of the second sign –Nick’s image as a criminal– that his original monoisotopy can be posthumously restored.

A similar role is played by Dawn’s photomontages offered to Emma and Sarah: while the represented situation does not constitute a “that has been”, the images are created from fragments of authentic circumstances that, when artificially reunited, can represent and make real a level of truth that exists beyond the binary true/false of authentication. As much as fiction can use fragments of reality to “speculate” scenarios and situations, the fictional imagetic construction occurring in this situation is aimed at representing a reality: another degree of truth accessible only through the digital substance in the interactions occurring between existential simulacra exchanging beyond the rules of the material world. The fictional manipulation of images appears as a tool to overcome the difficulties of the material world, utilising artificial mechanisms in the production of a creative act that is only sign: pure ideal, invested with the power of making real and making subject.

For Barthes (1980) and Susan Sontag (2002) this reversal in the roles of photography and reality constitutes a power of images to destroy the real, creating dynamics in which reality must become like images, which are “more alive” –more real– than we are. Once the “necessarily true” referent of photography is accepted as a partaken truth, then images can become the chosen medium to construct “truthful fictions”: fictional identities and narratives fashioned as successive instances of “that has been” that are assembled from authentic referents, but rearranged to tell stories that don’t belong, strictly speaking, to the substances and rules of “the real world”. As a result of these dynamics, we fully realise Barthes’ prediction of a reality in which enjoyment can only occur through images. Furthermore, the “necessarily real referent” of photograph-like artefacts as a given is the core feature enabling images to mask their own connotative nature –a cultural simulacrum or lying language, similar to Per Aage Brant’s (1992), Barthes’ (1984), and Greimas’ (1983) understanding of the verbal substance.

2. Veridiction and faire semblant: the contract of attention

The blurring of lines between “fictional” and “real” identities aligns with Paolo Fabbri’s definition of reality as an existential embrayage (Greimas & Courtés 1986:185), outlining the contrast of the conjunctive relation between the subject and the world installed by the discourse, and the effect of unreality [déréalité] as an existential débrayage, in which the subject seems to be expelled from the world. In Clickbait, the identity dynamics between characters respond to this process of unrealisation: the moments of expulsion are represented as corporeal reactions disseminating figures of dysphoric insights –the discovery of a “truth” that invalidates a character’s narrative trajectory to the point of its occurrence. Participation in the digital world has its origins in a complex response to this procedure of expulsion, presenting “reactions” to unrealisations that lead subjects to reverse their IRL thematic roles into digital catastrophic roles (Cf. Landowski 2005): a passage from the algorithmic logic of programming to the logic of hazard or the regime of accident, opposing their assigned roles as well as the ones assigned to other characters.

The semiotic definitions of identity and fiction share their reliance on the figure of the observer: an external agent who does not participate in the communication process but whose presence is a central element in producing the effect of real both in the fictional discourse and the process of construction and sanction of identity (Greimas & Courtés 1986). The observation, in both cases, has an effect on its object, transforming the doing of subjects into a “pretending”, a faire semblant: a given agent, aware of the presence of an observer, alters their behaviour to appear to do one action when, in reality, they either do not do it or do something else (Greimas & Courtés 1986). As such, when identities are manufactured with the observer in view, they cease to be the “fact of being who or what a person or thing is” –the dictionary definition of “identity”– to become a set of staged practices, behaviours, and self-presentation that are not authentic or truthful, but aimed at engaging the observer.

In Juan Alonso Aldama’s (2018) exploration of this regime, a faire semblant can be deployed as a replacement to the make-believe-true [faire-croire-vrai] in Greimas’ theory, thus enacting a transformation in the standard logic of veridiction. In this dynamic, the enunciator pretends to tell the truth (and that the enunciatee believes it); the enunciatee pretends to believe it; and, finally, the enunciator too pretends to believe they are telling the truth. A surface representation of this mechanism can be gauged in Clickbait’s interrogation scenes: the effect of flashback is offered to the audience as a manifestation of contradiction between what characters assert in the present verbal substance; and what they remember, revealed to the external enunciatee as something secret to the other characters. This contradiction creates the effect of lie: the verbal substance of the character’s speech (appearing) does not match the iconic substance of the character’s memory (being), showcased as moving images. In all cases, an expected behaviour –to be compliant and give a statement to the police, to speak to the media so as to show one has “nothing to hide”, and so forth– creates an effect of falsity that is used to preserve a “deeper truth”. When Pia and Sophie lie to Amiri about Nick’s violent behaviour, the (false) simulacrum of Nick as a model husband and brother is deployed to preserve another truth: even though two of the women experienced verbal and physical aggression from him, they refuse to accept that Nick would be capable of a crime of abuse and murder. Two equally false simulacra, perfect Nick and Nick as a monster, take turns competing for engagement in those interactions, with the aim of preserving the “real Nick”, now deceased, who exists in between distorted images that, through their multiplication, become realities in the course of the case. Similarly, Emma’s lying about being in a physical relationship with Nick protects the truth of her (real, authentic) feelings for “Nick” –the character created by Dawn– and her fantasies of what would have been “in another life”, had she and Nick ever met IRL. In the conflicts of simulacra created by the women in the narrative, to preserve the “truth of Nick” appears intersubjectively as a form of self-preservation: the identities of the women –as wife, sister, girlfriend– are dependent on the preservation of Nick’s identity as a good husband and father, a model brother, the ideal man.

Alonso Aldama’s (2018) conclusion that the regime of pretending occurs as a temporary contract is in line with a traditional theory of veridiction, in which the sanction of discourses as true (or otherwise) is the goal of the interaction between the enunciator and enunciatee: when pretending is mutually agreed, the end of the agreement coincides with the unmasking of the game itself –the revelation of the staging. However, the emerging veridictory logic represented in Clickbait doesn’t seem to obey the parameters of the traditional contract of veridiction: similar to the transformations examined by Lorusso (2021), Anouar Ben Msila’s (2021) analysis of the nudge exposes another instance of veridiction in which the mechanism of sanction is somehow invalidated through self-directed “soft incitation”, making operations such as manipulation lose their narrative pertinence. Contrary to the set of cultural dynamics forming the context in which Greimas’ theory of veridiction was formulated, the forms of faire semblant identified in today’s identity dynamics seem to constitute an attention-driven –rather than sanction-driven– scenario, in which engagement seems to matter more than adhesion: the validation of discourses no longer lies on the enunciatee’s final epistemic judgement of adequation but on a cultural text’s ability to sustain the enunciatee’s involvement.

Because the terminative aspect carried in the act of sanction has the power to end the engagement, it is no longer sanction (or Lorusso’s authentication) that carries the value: it is precisely the infinite suspension, the continuous capture of attention –the “infinite circularity” identified by Erik Bertin and Jean-Maxence Granier (2019)– that becomes the value. As such, even when one faire semblant is uncovered, thus bringing one dynamic to an end, another faire semblant takes its place so that the contract of attention can carry on. In other words, while Greimas’ schema of the veridiction contract presupposes that the sanction of truth through the terminative aspect is the goal of a make-believe-true, interactions governed by contracts of attention will rely on the postponement of the terminative aspect: its aim, instead, is an endless succession of durations. Such marks a transformation in which the value of the object (the discourse itself or that which it disseminates) is transferred to the subject (their engagement, measured through audience points or, in the online era, by clicks and “reactions”). While sanction can be applied only once, the potential for engagement can be infinite –as long as sanction is avoided.

Although this mechanism is well understood in the realm of fiction and, more recently, in media management, the extent to which the same dynamics are present in the realm of personal “identity management” is less discussed. The transformation in our semiotic relationship with signs affecting our consumption and sanction of information, facts, and communication channels disseminating these has also shifted our construction of subjectivity: embedded in the same logic of “reality creation”, our self-creation for an observer no longer relies on sanctions of belonging or presenting an adequate image to the world. Rather, the value of identity is measured by how much attention it can sustain, transforming sanction into a form of “self-assessment” in which subjects constantly search for engagement, adjusting their behaviour, self-presentation, and discourse.

One of the characteristics of attention-driven identities is that they cannot sustain multiple isotopies, constituting instead flat, successive unidimensional characters. In Clickbait, the clash of multiple monoisotopies forms the base of personal conflicts: initially appearing as characters embodying almost caricatural versions of their assigned thematic roles, the clashes in the plot emerge when the operational aspect of a single permitted narrative trajectory collides with a second programme. In all cases, the impossibility of a syntagmatic approach to identity in the model proposed by Fontanille (2004) creates polarised dynamics in which only one role can be true. Rather than accumulating trajectories that would enable subjects to construct themselves as complex ensembles of emotions and experiences, identities too are embodied and discarded in succession, mirroring the endless series of facts and stories in our social media feeds or the quasi-comical concatenation of conflicts in clickbait-style TV shows. In that sense, although those identities are not false, since they emerge, even if to a small extent, from fragments of genuine experience, they are neither authentic nor sincere: rather than expressing from the subject’s core, they are shaped aiming at the observer, thus constituting instances of faire semblant aimed at holding attention, which causes subjects to bend their own experiences to become more “cinematic” –both visually and narratively.

Through each character in Clickbait, we see another important aspect of this identity construction logic: the possibility of multiplication through identification, indicating a successful contract of attention has been established. Emma Beasley is an emblematic character representing the attention-oriented identity shifts so visible in today’s media landscape. Starting from an uncompromising assertion of her physical relationship with Nick (and the testament of his character), Emma’s aim is to hold attention to her identity as Nick’s girlfriend, taking the necessary steps to insert herself in the case as an “important person” in his life. In her interactions with the family and the police, we see her constantly eyeing the interlocutor, who plays the role of observer, to gauge if her performance is producing the expected reaction. Her behaviour responds to an eagerness to “be a part of his world”, striving to be perceived as part of the family, a participant –in the case, as well as in the suffering. It is not real Nick’s death that enacts Emma’s expulsion from reality, but the discovery of multiple similar relationships involving “Nick”: to know “she was not the only one” causes her to reverse into a victim. By adopting a role that grants her a space in the public eye, she becomes capable of holding collective attention, finally becoming a “person of interest”. Likewise, this special place gained through her reversal into a catastrophic role enacts Emma’s multiplication as more than one of Nick’s victims: she becomes every victim, activating the role of “abused woman” in every woman who watches and resonates with her story. A mechanism well understood in the realm of fiction –the identification with a character as a form of role model to real-life persons– the stories disseminated through Clickbait’s plot represent the possibility of a similar function being fulfilled by IRL stories, whether they are real or fictional.

Such transformations of identity are also strongly linked to Fabbri’s (Greimas & Courtés 1986) definitions of reality and unreality discussed above: the reversal of characters into catastrophic roles causes an identity shift that is aimed at regaining a status of reality. In Dawn’s interactions with the women, we first see the attempt at a self-initiated multiplication, which is disseminated as the creation of multiple Nicks, deployed in different dating websites, and using different false names (but the same photos, same stories, same “personality”). Rather than living multiple romances, it is the same love story, over and over again, that Dawn tries to sustain by suspending the moment of sanction –the unmasking of her profiles being fake. To sustain this temporary participation in a reality, Dawn goes as far as intruding in the IRL substance in her relationship with Emma: so as to prove her material reality as Nick, she sends Emma physical gifts for her birthday –a teddy bear, heart balloons, red roses, a card, and the print photo showing Emma and Nick together. Similarly to other intersubjective dynamics, this gesture also grants reality to Emma’s identity as a girlfriend, somehow providing her with a “physical display” of the relationship, allowing Dawn the chance to prolong the contract of attention established between them.

The character dynamics represented in Clickbait outline an argument in which the reality of a person or thing –its identity, if we return to the linguistic meaning of the word– is measured through the currency of attention. In that logic, to fail to sustain attention means to lose reality: to be expelled into the realm of unreality, which, at the subjective level, means to be existentially threatened. While Dawn and Emma are characters constantly fictionalising themselves into reality by trying out different identities, Simon Burton’s (“The Brother”) trajectory is marked by more consequential changes in isotopy. In the relationship with his sister, Sarah, he struggles to hold her attention, thus failing to sustain his reality as a brother. A social media content moderator, he uses his work privileges to spy on Sarah by activating her laptop camera and microphone remotely without her knowledge or consent. Unable to make his sister open up to him, his attempt to force access to her life marks an important distinction in his status, not as a participant but as a “watcher” of her life events –particularly the new relationship with “Nick”, which inflicts extreme highs and lows in her. Simon’s first expulsion from reality occurs when he watches his sister lying to him in a message while she is on the phone with “Nick” (Dawn, speaking through a voice distortion device). When he finds Sarah’s body in her apartment, he also finds her phone: rather than her death, it is the moment when he reads the text exchange between “Nick” and Sarah that enacts his second expulsion from reality and the discovery of his failure as a brother, despite all the surveillance.

In the plotting and implementing of his revenge against “the man in the photograph”, Simon strives to secure his entrance back into the realm of reality, reversing from brother (thematic) to vigilante (catastrophic). Through the public spectacle channelled by his video, Simon multiplies himself while enacting a multiplication of Nick. The simultaneous views quickly leading to the 5 million count cause “the author” to become every victim of injustice seeking revenge, a self-appointed “agent of justice”, while Nick also becomes an emblem of “every abuser”, activating a mass phenomenon of identification –personal or projected– with the story. However, in his face-to-face confrontation with the real Nick, and the realisation that he “caught the wrong man” causes Simon to be re-expelled from his newly gained access to reality, which is reiterated in his painful interaction with Pia, Nick’s sister, and the confession of his mistake.

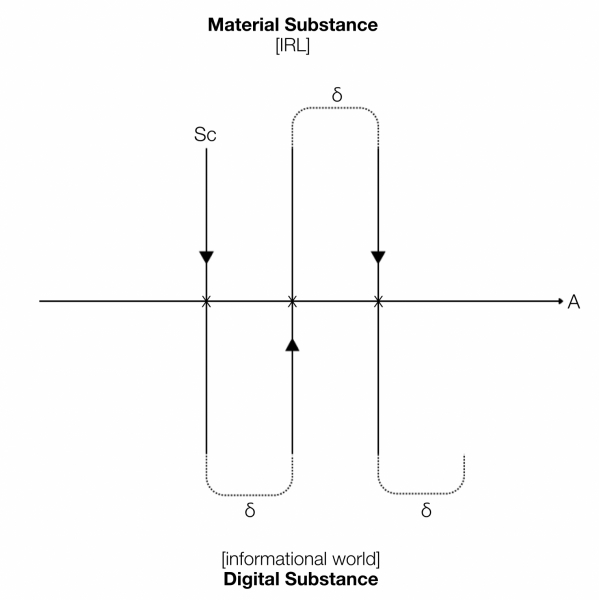

Figure 1. The trajectory followed by subjects and the successions of multiple identities necessary to negotiate a contract of attention across both discursive substances –the Material World (IRL) and the Informational World (life online). Although in the present analysis the real world is entangled with thematic roles and life online with catastrophic ones at the narrative level, this relation is not fixed: it is possible that, in other fictional artefacts (or real-life cases), the different substances would manifest a different narrative level. In Clickbait’s analysis, characters can both initiate the procedure (in Emma and Simon’s case, for example) or be forced into the trajectory (as occurs with Nick’s identity, even after his death); finally, it is also possible for identities to become entangled, and the trajectory of one identity will ripple in another (such as the presupposed pairs husband-wife, brother-sister, boyfriend-girlfriend explored in the plot). The horizontal line A represents the durative aspect, which is constituted by zones of faire semblant (δ) where subjects transform their identity to embody a new role. The vertical lines (Sc) constitute the disruption of the terminative aspect coinciding with the moments in which the subject either seeks or is forced into a procedure of sanction, ending sections of durative attention in the subject’s trajectory. X marks the point of unrealisation of the subject who is expelled from one substance into the other, triggering the new process of transformation.

Conclusion

Throughout the analysis, I aimed to dissect the representation of identity construction in a logic of attention and its appropriation of procedures identified with fictional texts. A commentary on a phenomenon gauged in our current cultural context, the transformation in how identities are formed is affected by the same shift in the veridictory logic governing discourses in an age of ubiquitous mediation and its quantitative, algorithmic models of measuring existence as synonymous with visibility and engagement: to be real is to be mediatised, to be viewed, shared, and reacted to. In this logic, more than individuals, each character becomes a simulacra of a role, models that can be replicated and adopted to help others shape their own identities and make sense of life, mirroring fictional mechanisms permitting the enunciatee to identify themselves and others with characters in a story. In this case, however, it is mediated reality playing the role that once belonged to fiction: rather than characters created by an author, self-created “real” people (deploying different degrees of “good” and “bad” fiction...) become imprints of identification and projection.

This phenomenon gives a compelling representation and commentary to the theme of blurred lines between genres, as well as elements of what is fictional, what is information, and what is reality, remarked by Lorusso (2012): all become equivalent and acceptable ingredients in the crafting of lives that exist between reality and unreality, virtual and real, material and digital. In its turn, this dynamics causes subjects to rely on highly thematised structures forming the base of existential simulacra aimed at engagement, utilising such narrative trajectories as “lie-producing mechanisms” mirroring the roles Barthes (1984) and Brandt (1992) attribute to the linguistic substance: the construction of identity, in reality and fiction, is a connotative doing –even if it gives itself as a straight, binary structure of truth (authenticity or sincerity) and lie. Equally, this fragmentary connotative doing supports the temporary logic of faire semblant, which becomes the standard of interactions once the final aim of texts, discourses, and human interactions themselves shift from the pursuit of sanction to the goal of sustaining attention. As a consequence, the binary structure of truth and lie loses its pertinence: in a model in which communication and interaction take place as a confrontation of cultural simulacra, it is only a personal and intuitive (rather than partaken and cognitive), temporary sanction that plays any role in a contract of attention.

In returning to the symbolic cultural logic identified by Lotman (1973), in which the sign takes precedence over the real, the creation of signs as what can “make subject” causes images to become a privileged mechanism of reality-making –rather than a form of “representation”–granting those iconic artefacts with the power of producing and evidencing truth, even when what they show is fictional. Rather than a cumulative construction of life experiences, identity becomes a course of existential imprints that cannot constitute totalities but only an infinity of attention-sustaining punctualities with no end. An important (narrative) consequence of this model is that, in the effort to suspend sanction, texts –fictional, as well as real intersubjective exchanges– reject the procedure of catharsis in the Aristotelian model. To sustain engagement, the moment of revelation must be suppressed altogether, creating dynamics in which there is no release: only a perpetual cycle of suspensions and successions.