Smoke and mirrors: how the theory of “parental alienation” concealed domestic abuse and coercive control in France Un écran de fumée : comment la théorie de « l’aliénation parentale » a occulté la violence conjugale et le contrôle coercitif en France

In France, at the end of the 1990s, the concept of “parental alienation” appeared in court decisions relating to parental separations and became part of the discursive repertoire of family law. This article sets out to show the consequences of this concept’s use. A multi-method study (textual analysis of the press, quantitative and qualitative analysis of case law, analysis of promoters' strategies, interviews with mothers) is used to analyse these uses. Discourses on the “rights” of fathers and false accusations of incestuous sexual violence provide fertile ground for the spread of the concept. It is not possible to distinguish “parental alienation” from domestic abuse, due to the scientific invalidity and ideological nature of the associated criteria, and the fact that it remains faithful to Richard Gardner's controversial approach. Analysis of sociological interviews with women accused of “parental alienation” shows that their maternal strategies of protection against their ex-partner's coercive control are interpreted as parental alienation. They are likely to lose the children's residence, and live under the threat of losing it. This institutional violence is the result, on one side, of confusion between the interests or protection of the child and co-parenting and, on the other side, of the concealment of post-separation conjugal violence.

En France, à la fin des années 1990, la notion d’« aliénation parentale » apparaît dans des décisions judiciaires relatives aux séparations parentales et devient un élément du répertoire discursif du droit de la famille. Cet article propose de montrer les conséquences de l'usage de cette notion. Une étude multi-méthodes (analyse textuelle de la presse, analyse quantitative et qualitative de la jurisprudence, analyses des stratégies des promoteurs, entretiens avec des mères) permet d'analyser ces usages. Les discours sur les « droits » des pères et les fausses accusations de violences sexuelles incestueuses forment un terreau favorable à la diffusion de la notion. Elle ne permet pas de distinguer l’« aliénation parentale » de la violence conjugale, en raison de l’invalidité scientifique, du caractère idéologique des critères associés et de la fidélité à l'approche pourtant controversée de Richard Gardner. L’analyse d’entretiens sociologiques auprès de femmes accusées d’« aliénation parentale » montrent que leurs stratégies maternelles de protection face au contrôle coercitif de leur ex-conjoint sont interprétées comme de l’aliénation parentale. Elles sont susceptibles de perdre la résidence des enfants, et vivent sous la menace de la perdre. Cette violence institutionnelle est la conséquence, d’une part, de la confusion entre intérêt ou protection de l’enfant et coparentalité, d’autre part, de l’occultation de la violence conjugale post-séparation.

En Francia, a finales de los años 90, el concepto de "alienación parental" apareció en las decisiones judiciales relativas a las separaciones parentales y pasó a formar parte del repertorio discursivo del derecho de familia. Este artículo pretende mostrar las consecuencias de la utilización de este concepto. Para analizar estos usos se utiliza un estudio multimétodo (análisis textual de la prensa, análisis cuantitativo y cualitativo de la jurisprudencia, análisis de las estrategias de los promotores, entrevistas con madres). Los discursos sobre los "derechos" de los padres y las falsas acusaciones de violencia sexual incestuosa constituyen un terreno fértil para la difusión del concepto. No permite distinguir la "alienación parental" de la violencia doméstica, debido a la invalidez científica y al carácter ideológico de los criterios asociados, y al hecho de que se mantiene fiel al controvertido enfoque de Richard Gardner. El análisis de entrevistas sociológicas con mujeres acusadas de "alienación parental" muestra que sus estrategias maternales de protección contra el control coercitivo de su ex pareja se interpretan como alienación parental. Es probable que pierdan la residencia de los hijos, y viven bajo la amenaza de perderla. Esta violencia institucional es el resultado, por una parte, de la confusión entre el interés o la protección del menor y la coparentalidad y, por otra, de la ocultación de la violencia conyugal posterior a la separación.

Em França, no final dos anos 90, o conceito de "alienação parental" apareceu em decisões judiciais relativas a separações parentais e passou a fazer parte do repertório discursivo do direito da família. Este artigo tem por objetivo mostrar as consequências da utilização deste conceito. Um estudo multimétodo (análise textual da imprensa, análise quantitativa e qualitativa da jurisprudência, análise das estratégias dos promotores, entrevistas com mães) é utilizado para analisar estes usos. Os discursos sobre os "direitos" dos pais e as falsas acusações de violência sexual incestuosa constituem um terreno fértil para a difusão do conceito. Não permite distinguir a "alienação parental" da violência doméstica, devido à invalidade científica e ao carácter ideológico dos critérios associados, e ao facto de se manter fiel à abordagem controversa de Richard Gardner. A análise de entrevistas sociológicas com mulheres acusadas de "alienação parental" mostra que as suas estratégias maternas de proteção face ao controlo coercivo do ex-companheiro são interpretadas como alienação parental. Elas correm o risco de perder a residência das crianças e vivem sob a ameaça de a perder. Esta violência institucional resulta, por um lado, da confusão entre os interesses ou a proteção da criança e a co-parentalidade e, por outro, da dissimulação da violência conjugal pós-separação.

Introduction

Violence against women is a violation of their human rights and a global public health concern. It is estimated that 27% of women aged 15-49 who have ever had a partner have experienced physical or sexual abuse, or both, from an intimate partner in their lifetime (Sardinha et al., 2022). Intimate partner violence “refers to physically, sexually, and psychologically harmful behaviors in the context of marriage, cohabitation, or any other form of union, as well as emotional and economic abuse and controlling behaviors” (Sardinha et al., 2022: 804). It manifests itself in different ways depending on the social, economic and political circumstances that limit women’s ability to leave violent relationships, such as economic insecurity or gender inequitable norms, the state of family law and the availability of support services (Sardinha et al., 2022: 811).

- Note de bas de page 1 :

-

The term was first used during the Cold War in the Miami News in September 1950 by journalist Edward Hunter.

At the end of the twentieth century, when violence against women and children is denounced, emerged in several Western countries allegations of “parental alienation,” a notion presented as relevant (Mercer & Drew, 2022). Discourses claiming to be scientific evolve according to socio-political contexts. Today, the work defending the notion continues to be based on the theories of the American psychiatrist Richard Gardner. His books, most of which were self-published by his company Creative Therapeutics, were aimed at advising mental health and legal professionals and divorced parents, mainly men. The idea of parental manipulation is germinating around the notion of brainwashing1 in Gardner’s early publications on divorce:

- Note de bas de page 2 :

-

This book was translated into French in 1979.

A related alteration of thinking that I have found useful to attempt to effect in children with anger inhibition problems is what I refer to as ‘changing your mind about the person you’re angry at.’ The most common example of this is the child who has been brainwashed by one parent into believing that the other parent is the incarnation of all the evil that ever existed in the world (Gardner, 1977: 250).2

Based on his clinical experience, he defines parental alienation syndrome as “childhood disorder that arises almost exclusively in the context of child-custody disputes” (Gardner, 2002: 95). According to the author:

its primary manifestation is the child’s campaign of denigration against a parent, a campaign that has no justification. It results from the combination of a programming (brainwashing) parent’s indoctrinations and the child’s own contributions to the vilification of the target parent (Gardner, 2002: 95)

- Note de bas de page 3 :

-

In its FAQ on the Classification, the WHO states that it has not included it “because it is not a health care term. The term is rather used in legal contexts.” While the WHO states that “parental alienation is an issue relevant to specific judicial contexts,” it points out that “there are no evidence-based health care interventions specifically for parental alienation.” https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/frequently-asked-questions/parental-alienation

However, the process called “parental alienation” is not scientifically recognized (Milchman et al., 2020). It is not listed in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), nor in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases.3 Richard Gardner’s particular views on atypical sexuality and paedophilia, revealed at the end of the 1990s (Dallam, 1998), should have been enough to discredit his theory. Why, then, does it continue to be used in a social context where the fight against what is now called “paedocriminality” in France has become a major social issue? (Verdrager, 2021)?

- Note de bas de page 4 :

-

The SOS les Mamans association (2008-2018) makes these situations visible.

- Note de bas de page 5 :

-

DACS-Flash, 28 March 2018, “Le syndrome d’aliénation parentale [Parental alienation syndrome]”, p. 2.

The “syndrome” and “parental alienation” are gradually being mentioned in political and media debates on parental separation and children’s custody, and are spreading from one country to another in the legal system. In France, the concept of “parental alienation” appeared in court rulings on parental separation in the 2000s. The emergence of testimonies from mothers reveals how violence is concealed by the use of this concept4 (Durand, 2013; 11 specialist associations, 2018). As a result, an internal memo to magistrates in 2018 stated that “in the absence of official recognition, PAS is the subject of controversy.”5 This recommendation to stop using it follows the fifth plan to mobilize and combat all forms of violence against women and the action taken by Senator Laurence Rossignol, who was Minister at the time. Recent international research shows the consequences of its use in family courts: it hinders the consideration of situations of violence (Meier, 2020; Birchall & Choudhry, 2022; Dalgarno et al., 2024).

In this article, we look back at the way the concept has been disseminated in France, then discuss the various definitions given, highlighting their shortcomings and contradictions. Finally, we present an analysis of interviews with women accused of “parental alienation,” as part of a multi-method study (textual analysis of the press, quantitative and qualitative analysis of case law, analysis of promoters’ strategies) on the social uses of the concept.

The emergence of the concept of “parental alienation” in France

Discourses on fathers’ “rights” and false accusations of sexual abuse: a fertile ground for the dissemination of the theory

- Note de bas de page 6 :

-

DIDHEM is an acronym that stands for Défense des intérêts des divorcés hommes et de leurs enfants mineurs (Defence of the interests of divorced men and their minor children). The association was set up in Grenoble on 15 November 1969, following the Cestas criminal case (Sueur, 2020).

The discursive strategies of fathers' groups contribute to disseminate the notion. From the early 1970s, the first association of divorced fathers, DIDHEM,6 developed anti-feminist discourse on women’s greed, co-responsibility for domestic abuse, and the idea of false accusations at the time of divorce (Sueur, 2019). The fathers’ movement uses the law and turns to legislators to reassert power and control after separation.

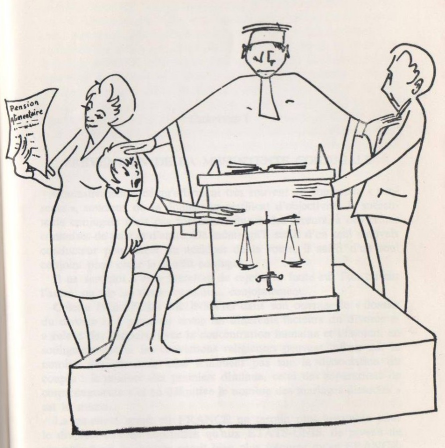

Gwénola Sueur documents how the association describes in filigree the concept of parental alienation as “the alteration of the image of one or other of the parents, especially without just cause, in the mind of the child” (DIDHEM, 1973: 186) and considers that when “the child, especially in infancy, is glued to the mother from the beginning of divorce proceedings [this] often results in the alienation of the father” (Sueur & Prigent, 2022: 105). Divorce is portrayed as a curse, and caricatures illustrate the “exclusion” of fathers through the courts and portray mothers as venal wives (Figure 1).

Figure 1: DIDHEM’s caricature

Extract from DIDHEM, 1973: 191. In this drawing, a magistrate separates the child from his father. They both look sad. The mother, smiling, holds the child in one hand and holds a document entitled “alimony” in the other.

- Note de bas de page 7 :

-

In its magazine, SOS Papa explains, for example, that “in the absence of effective safeguards, the ‘Milgram effect’ and the ‘Stockholm syndrome’ lead to the persecution of the non-custodial parent, especially the father, and to the destruction of the child;” SOS Papa Magazine, April 1992, “Une thèse de la commission des études psycho-sociologiques de SOS Papa. Anatomie d’une tyrannie [A thesis by the SOS Papa psycho-sociological studies committee. Anatomy of a tyranny]”, p. 8.

- Note de bas de page 8 :

-

Law no. 2002-305 of 4 March 2002 on parental authority.

Twenty years later, the association SOS Papa, founded in 1990, organises conferences on what they call “discrimination” against fathers and false accusations in the context of parental separation. Fathers’ “rights” campaigners were looking for apparently scientific concepts to pathologize mothers and children and portray themselves as victims of the law, women and feminists.7 They obtained hearings at the Ministry of Justice and worked to influence the drafting of the law of 4 March 2002,8 which legalized joint custody and could be imposed at the request of a single parent, and in which co-parenting became a principle in family courts, without taking any real account of domestic abuse (Prigent & Sueur, 2019).

The rhetorical devices and strategies identified by legal researchers Miranda Kaye and Julia Tolmie can be found among the French groups, particularly the language of equality and rights, the use of anecdotes and statistics, the claim to victim status, and the negative depiction of women (Kaye & Tolmie, 1998). While their demands evolve and adapt to current events, their main demands concern the imposition of a restricted geographical area after separation, the prioritization of joint custody, and coercive measures against their ex-spouses (recognition of the concept of parental alienation, transfer of custody in the event of relocation, conviction for failure to present a child). Depending on the context and the resources of both parents, they may enable abusive men to maintain power and control over their ex-spouses and children after separation (Table 1).

Table 1: A table paralleling the tactics of abusers, what the fathers’ movement is demanding and the consequent benefits for abusive men

|

Abusers' tactics |

What the fathers' movement is demanding |

Benefits for the abusive men |

|

Patriarchal control of daily activities Intimidation |

Co-parenting and joint custody without safeguards under the Law of 4 March 2002 |

Frequent contact with the ex-partner and children (telephone, Internet, children’s visits) Supervision of day-to-day decisions relating to the children |

|

Isolation Deprivation of resources Intimidation |

Imposing joint custody at the request of one parent Considering relocation as an obstacle to co-parenting |

Prohibit relocation under penalty of transfer of residence Control of space |

|

Isolation Deprivation of resources Intimidation Overburden of responsibility |

Increase the number of convictions for failure to represent a child and request the transfer of residence on the basis of this conviction File complaints against those who support women |

Use coercion when victims resist control Use reprisals: transfer of residence or threat of transfer of residence |

|

Overburden of responsibility Devaluation Confusion |

Disseminate the idea that accusations of violence are usually false Get parental alienation recognized |

Silencing the victims To discredit them |

First presented on 4 March 2017, and updated as our research continues.

- Note de bas de page 9 :

-

L'Express, 15 April 1999, “L'arme du soupçon d'inceste [The weapon of suspicion of incest].”

- Note de bas de page 10 :

-

An extract from an article by Hubert Van Gijseghem was published in SOS Papa Magazine, June 1995, “Fausses allégations d'abus sexuels dans les causes de divorce, de garde d'enfants, de droits de visite [False allegations of sexual abuse in divorce, custody and access cases].”

In France, the concept of parental alienation appeared explicitly at the end of the 1990s. Situations of incest began to be covered by the media in the 1980s. Stories were reported to the Viols femmes information [Rape Women Information] hotline, which became operational in 1986 (Boussaguet, 2009). Divorced fathers received media coverage and presented themselves as victims of false accusations of sexual abuse. A dossier in the April 1999 issue of L’Express presented the “parental alienation syndrome”9 through the intermediary of Hubert Van Gijseghem, a Belgian-Canadian psychologist and expert. He acted as a “private expert” in the case of one of the fathers, and concluded that there was a “parental alienation syndrome.” His writings focus on false accusations of sexual abuse,10 and since 1995 he has been training social workers and magistrates in France and Europe (Belgium, Switzerland).

The movement to defend the interests of divorced fathers used the opportunity to put forward estimates ranging from 50% to 92% of false accusations, described in L’Express as “the ultimate weapon, the atomic bomb of conflictual divorces, which is guaranteed to keep the ex-spouse away from the children for a very long time.” Enveff, the first national survey on violence against women carried out in 2000, showed that the rate of domestic abuse in the context of separation is particularly high (Jaspard, 2011: 39). Separation was therefore presented as the context in which women make false accusations before being considered as a period of risk.

Richard Gardner and child sexual abuse: a cumbersome legacy

Articles in English on allegations of sexual abuse are published at the same time as those on parental alienation. These studies, which are not very rigorous and are based on very small samples (for example, Green, 1986, on only 11 cases), suggest that a significant proportion of such accusations, or even the majority of them, are mostly false in the context of parental separation. Gardner theorises that “a false sex-abuse accusation sometimes emerges as a derivative of the PAS” (Gardner, 2002: 106). Taking up this idea of the massiveness of false accusations, he states that “a mother’s allegation of child sex abuse became a very powerful weapon” (Gardner, 1991: 24), or even “a very effective method of wreaking vengeance on a hated spouse and will certainly speed up the court’s dealing with the case” (Gardner, 1991: 4). What’s more, he describes scenes of physical promiscuity in which children are made responsible:

A three-year-old girl and her four-year-old brother are taking a shower with their father. In the course of the frolicking, each child might entertain a transient fantasy of putting the father’s penis in his (her) mouth. Considering the relative heights of the three individuals, and considering the proximity of the children’s mouths to the father’s penis under these circumstances, it is not surprising that such a fantasy might enter each of the children’s minds (Gardner, 1991:11).

This description could correspond to a grooming context (see Stroebel et al., 2013: 599) and not to the child’s fantasies of performing oral sex on his parent. Or, Gardner romanticizes the behavior of child sex abusers:

With regard to such bedtime encounters, it is important for the evaluator to appreciate that most pedophiles do not rape their subjects. Rather, the more common practice is to engage in tender, loving sexual encounters during which the child is praised and complimented. The statements are very much like those made by a lover to his girlfriend. However, in addition to statements about how lovely, wonderful, and adorable she is, also included are comments related to her youth, e.g., ‘You’re my baby,’ ‘You’re my baby doll,’ and ‘You’re my lovely little baby’ (Gardner, 1992: 401).

- Note de bas de page 11 :

-

Le Point, 16 April 2022, “Inceste : ‘La cause des enfants est trop noble pour être confiée aux seuls militants’ [Incest: 'The cause of children is too noble to be left to activists alone’].”

- Note de bas de page 12 :

-

La Vie, 24 June 2024, “Marie-France Hirigoyen : ‘l’aliénation parentale constitue un traumatisme aux effets dévastateurs’ [parental alienation is a trauma with devastating effects].”

Despite his analyses, proponents of the notion persist in minimizing Gardner’s views on pedophilia. American psychiatrist William Bernet, president of the Parental Alienation Study Group, declares that his writings have been “taken out of context” (Bernet, 2020, p. 295). Paul Bensussan, a psychiatrist and expert approved by the Cour de cassation, says that “the worst that can be attributed to him is, to my knowledge, to have said that incest existed in all civilizations.”11He adds that he “disagrees with [him] on just about everything"” having nevertheless adopted his criteria for defining a phenomenon of parental alienation (Bensussan, 2021: 30-31). Psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Marie-France Hirigoyen denounces the “denial” of parental alienation, associating it with the “supposedly unhealthy figure of Richard Gardner [...] to create a repulsor and disqualify the whole notion.”12

What about the “false accusations”?

The scientific literature shows that “reports of violence [against minors] made during the separation phase are not frequent and are very rarely false” (Romito & Crisma, 2009: 33). Lisak and colleagues, in their meta-analysis of false allegations of sexual abuse (committed against both minors and adults), show that they are between 2 and 10% (Lisak et al., 2010). It is pointed out that in some studies, the high rate of false allegations is explained by the lack of distinction between allegations that are insufficiently characterized and deliberately false allegations. In addition, sexual abuse in childhood affects a large number of people.

The Inserm-Ciase study (Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale - Commission indépendante sur les abus sexuels dans l’Église [National Institute of Health and Medical Research - Independent Commission on Sexual Abuse in the Church], carried out in 2021 in France, shows that sexual abuse perpetrated before the age of 18 affects 13% of women and 5.5% of men; for 4.6% of women and 1.2% of men, it involves incest. Around 8% report the incidents to the police or the courts. Examination of cases of sexual abuse against minors tried as misdemeanours shows that disclosures to the courts are the latest and the most difficult. Thus, “the age of the child and the closeness of the relationship with the perpetrator are factors that are far from neutral and determine the conditions under which the offence is disclosed and brought to justice” (Romero, 2020). Separation is precisely the right time to report violence, whether sexual or domestic. The Virage survey, carried out in 2015 by Ined (Institut national des études démographiques [National Institute of Demographic Studies]), shows that around a third of women separated from their partner in the last twelve months report violence from their partner during this period, and one in six after the separation, with women who have had children with their ex-partner being more affected (Brown & Mazuy, 2022).

Contemporary definitions of parental alienation

Attempts to build consensus

- Note de bas de page 13 :

-

Olga Odinetz, 10 December 2022, “Lettre ouverte à l’ONU [Open letter to the UN].”

https://www.acalpa.info/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Lettre-ouverte-a-lONU-par-Olga-Odinetz-Acalpa.pdf

After a first period in which the notion of parental alienation was explicitly associated with false accusations of incestuous sexual abuse, it then spread through discourses that extended it more generally to conflictual separations. ACALPA, the association against parental alienation, was founded in 2004 and spread the concept in a less polemical way, arguing over time that fathers and mothers are equally concerned by this phenomenon.13 As a sign of its gradual institutionalization, a 2008 report by the Children’s Ombudsman Dominique Versini mentions manipulation and parental alienation syndrome before going on to discuss violence against women and children (Versini, 2008: 55-59).

- Note de bas de page 14 :

-

SOS Papa Magazine, September 1999, “8ème Congrès SOS Papa [8th SOS Papa Congress].”

In France, Paul Bensussan has been taking up Hubert Van Gijseghem’s clinical contributions since 1999, whether at conference where he has been invited by the SOS Papa association to discuss false allegations of sexual abuse,14 or in his books (Bensussan, 1999). He defines parental alienation as “any situation in which a child unjustifiably rejects a parent - at the very least not explicable by the previous quality of the relationship” (Bensussan, 2021: 28), and may also speak of “parental disaffection”, or even “loyalty conflict, reserving the term ‘parental alienation’ for the most extreme situations” (Bensussan, 2021: 38).

Drawing on Richard Gardner’s three-stage distinction, Bensussan suggests that, in case of “severe” parental alienation stage, the child’s residence should be transferred to the home of the “alienated” parent, sometimes “after a short period of temporary placement, acting as a veritable ‘deconditioning airlock’” (Bensussan, 2021: 37). Forensic expert Jean-Marc Delfieu proposes “the reversal of rights to the exercise of parental authority [which] is the most effective method.” He explains, again drawing on Gardner, that “a child can withstand the transfer from one parent to the other, whereas the damage caused to his or her quality of life by prolonged exposure to manipulative behavior by one parent is much more serious and lasts a lifetime” (Delfieu, 2005: 30).

The “therapy” proposed in the event of a diagnosis of “severe” parental alienation is thus not, strictly speaking, a medical treatment, but a judicial coercion of the parent qualified as “alienating”, and of the children. Paul Bensussan asserts that “knowing how to distance oneself from the child’s word comes down to the possibility of forcing him or her, legally if necessary, to visit the rejected parent” (Bensussan, 2021: 39).

Gardner’s contradictory criteria

In order to identify and measure the seriousness of the situation of “parental alienation,” the French promoters of the notion take up Richard Gardner’s eight diagnostic criteria:

1. A campaign of denigration 2. Weak, absurd, or frivolous rationalizations for the deprecation 3. Lack of ambivalence 4. The ‘independent-thinker’ phenomenon 5. Reflexive support of the alienating parent in the parental conflict 6. Absence of guilt over cruelty to and/or exploitation of the alienated parent 7. The presence of borrowed scenarios 8. Spread of the animosity to the friends and/or extended family of the alienated parent (Gardner, 2002: 97)

These criteria were taught at the École Nationale de la Magistrature until recently, or in schools of social work. But these criteria suffer from major shortcomings. They constitute circular reasoning and prevent the consideration of explanations other than maternal indoctrination. Factually denouncing abuse or neglect by the abusive parent can be considered as denigration of the latter, or of his or her parenting skills. The “independent thinker” criterion, on the other hand, is contradictory: if the child declares that he has his own opinions, this is an indication that he is being manipulated. What’s more, accounts of events experienced by the mother and repeated by the child could be qualified as borrowed scenarios in this respect.

The terms “weak”, “absurd” and “frivolous” are subjective and cannot guarantee a supposedly coherent and reliable diagnosis, built on precise and clear criteria. The same applies to the term “unjustified” (Bensussan, 2021: 28). Richard Gardner conceded that “when bona fide abuse does exist, then the child’s responding alienation is warranted and the PAS diagnosis is not applicable” (Gardner, 2002: 95). Paul Bensussan points out that “parental alienation must be excluded in cases of abuse and/or proven affective deficiencies during the time they lived together” (Bensussan, 2021: 28). Hubert Van Gijseghem, for his part, asserts that “there are certainly child-parent distanciations that cannot be qualified as parental alienation, because they are justified, i.e. motivated by actions on the part of the parent that have prompted the child, if not the protective or judicial system, to create this distance” (Van Gijseghem, 2016: 454). Even so, the lack of clarity in the diagnostic criteria is an obstacle to truly taking into account a context of violence.

When Gardner describes the clinical manifestations of parental alienation syndrome in alienating mothers (Gardner, 1998: 132-156), he is actually describing the protective strategies put in place by women who are victims of domestic abuse, such as moving out, refusing to present the child to the father, describing his behavior as harassment, or being sheltered by an association that helps abused women. At the same time, he recognized that “there are some genuinely abusing and/or neglectful parents who will indeed deny their abuses and rationalize the children’s animosity as having been programmed by the other parent” (Gardner, 2002: 100).

The inevitable confusion between parental alienation, domestic abuse and coercive control

Abusive fathers can have a negative impact on children’s well-being, mental health and development. They are likely to be authoritarian, rigid, neglectful, uninvolved and/or overly permissive parents, self-centered, capable of criticizing the mother’s parenting abilities, instrumentalizing children and at high risk of perpetrating physical and emotional violence against them (Bancroft et al., 2012; Sadlier, 2016). One of the main risk factors for child sexual abuse by the father is domestic abuse against the mother (Stroebel et al., 2013), and that 40% to 60% of husbands who are violent with their wives are also fathers who are violent with their children (Herrenkohl et al., 2008), although the range is greater depending on the survey. Pioneering studies on children in domestic abuse indicate that mothers and children talk to each other about the violence they have experienced (McGee, 2000: 95-110).

At the same time, advocates of the parental alienation theory (both French- and English-speaking) assert that it falls under the heading of “psychological abuse of a child” (Bensussan, 2021: 33), define parental alienation as “family violence” or even “coercive control” (Harman et al., 2018), or “a severe form of psychological child abuse” (Boch-Galau, 2018: 111). The notion of “parental detachment” is used to refer to “the justified rejection of a parent following an actual history in the form of abandonment, abuse, sexual abuse or domestic abuse” (Boch-Galau, 2018: 111). However, among the alienation techniques used in cases of “parental alienation”, psychological and physical violence are retained, yet are supposed to justify the rejection of a parent. This inevitably leads to confusion between situations where rejection is justified (“parental detachment”) and those where rejection is unjustified (“parental alienation”).

- Note de bas de page 15 :

-

“Emprise” is difficult to translate into English. “Entrapment,” the literal translation, refers more to the theory of coercive control (Stark, 2023), while “emprise” has more to do with psychoanalytic theory.

The same criticism can be addressed to Marie-France Hirigoyen’s conceptualization of the phenomenon. She has been defending the use of the theory of parental alienation since her early works on the dynamics of partner abuse, which she theorizes as “emprise”15 (Hirigoyen, 2006: 269). To distinguish rejection linked to abuse from rejection linked to parental alienation, she points out that children generally perceive the “rejected” parent in an ambivalent way, “whereas alienated children generally tend to cleave and completely lack ambivalence towards their parents” (Hirigoyen, 2024: 139). Since ambivalence is not systematic in either situation, how can we distinguish between them? According to the psychiatrist, parental alienation “is rarely the consequence of a parent’s conscious manipulation. Indeed, it is not so much the alienating parent who is toxic as the relationship he or she establishes because of his or her psychological difficulties” (Hirigoyen, 2024: 140). But how do you determine that the manipulation is “unconscious”?

She describes it as “one of the most serious forms of psychological child abuse” (Hirigoyen, 2024: 142), and uses Richard Gardner’s eight diagnostic criteria (Hirigoyen, 2024: 143). According to her, this is a “trauma with devastating effects on the child’s identity construction and psycho-affective development” (Hirigoyen, 2024: 145). Even though the theory is not supposed to be used in cases of violence, it qualifies as parental alienation situations where fathers would exercise it as follows: “these are most often controlling men who have subjected the mother to intimate terrorism, and who continue the coercive control after separation by using the child” (Hirigoyen, 2024: 90). She calls women who exert coercive control over men “alienating mothers”; according to Hirigoyen, they perform a “platonic incest” (Hirigoyen, 2024: 93) aimed at forming a couple with the child and excluding the father as a third party. Without ever presenting her methodology in detail, she confuses coercive control by mothers with parental alienation.

- Note de bas de page 16 :

-

Marie-France Hirigoyen advocates the use of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (Hirigoyen, 2024: 140; Bernet et al., 2020), to which the same criticisms can be levelled as above.

More recently, English-speaking proponents of this theory’s use have attempted to construct new models that are supposed to better identify situations of “parental alienation”. Recent quantitative studies (e.g. Baker & Chambers, 2011; Baker & Eichler, 2016) construct question titles that are based on, or even repeat, Richard Gardner’s diagnostic criteria: for example, “making negative comments”. Only one of these criteria would indicate the presence of parental alienation. The context in which these a priori alienating behaviors take place is not questioned. Even when questions are asked about possible violence, the labels supposedly relating to a phenomenon of “parental alienation” are not considered as being able to relate in reality to a more general context of violence. The authors of these studies, like those of studies published in French, do not propose a tool for distinguishing situations of parental alienation from situations of domestic abuse. Moreover, only proponents of the use of theory (Baker, 2018), such as members of the Parental Alienation Study Group, are consulted to evaluate these models. The most recent, the Five-Factor Model (Bernet & Greenhill, 2022), lists the following indicators likely to contribute to parental alienation: contact refusal on the part of the child towards the “rejected” parent, a good previous relationship, absence of mistreatment, alienating behaviors of the “favored” parent, and behavioral signs of alienation in the child. The latter are still based on Richard Gardner’s unvalidated criteria.16

Women accused of parental alienation while victims of domestic abuse

Methodology

The consequence of these theoretical weaknesses is that the “parental alienation” explanation for a child’s estrangement from a parent is used whether abuse is involved or not. In France, not a research had yet focused on the social uses of the notion of parental alienation. By conducting sociological interviews with separated mothers accused of being alienating, we wanted to understand the context in which such an allegation emerged, and to analyze its consequences. We had two hypotheses: on one side, given the multiplication of its uses, the notion of parental alienation could be mobilized in cases of domestic abuse, and not just incest. On the other side, because of the criticism it receives and the wider stereotypes associated with it (the manipulative mother), accusations can also be implicit.

Semi-structured interviews with twenty women were conducted between 2018 and 2021, by telephone or videoconference. They lasted an average of one hour and twenty minutes. The majority of the women were aged between 35 and 50. Two-thirds belong to higher socio-professional categories, and almost all are French. Three quarters have entrusted us with documents (judgments, expertises, attestations, photographs, videos, sound recordings, e-mails, text messages). We meet them through adverts on the social networks Twitter and Facebook, and in forums or Facebook discussion groups dedicated to health, couples, families or psychology, with a view to diversifying recruitment. We do not mention domestic abuse in these adverts, as we are seeking to verify whether the accusation of parental alienation is associated with it. In this sensitive field (Prigent, 2024), we need to adopt a suitable posture and build the trust needed to conduct interviews. Women can contact us again later if they wish, especially as their situation is likely to change.

To identify and understand domestic abuse, we use the model of the aggressor’s strategy. In France, the Collectif féministe contre le viol [Feminist Collective Against Rape] (Casalis, 2021) identifies five priorities for the aggressor: isolation, denigration, the inversion of guilt, the creation of a climate of fear and insecurity, and the organization of impunity. We also mobilize the notion of coercive control (Stark, 2023); based on interviews with women with children separated from abusive partners, Pierre-Guillaume Prigent identifies eight gendered and intertwined tactics used by abusers: isolation, deprivation of resources, patriarchal control of daily activities, intimidation, devaluation, confusion, overburden of responsibility and violence (Prigent, 2021). Coercive control continues to be exercised after separation, including against children (Prigent & Sueur, 2025, in press). It manifests itself particularly in the form of “ongoing, willful pattern of intimidation of a former intimate partner including legal abuse, economic abuse, threats and endangerment to children, isolation and discrediting and harassment and stalking” (Spearman et al., 2023: 1225).

Key facts of the study

Analysis of the interviews shows that these mothers are accused of being alienating, even though they are victims of domestic abuse that continues after separation. The interviewees talk about control and domestic abuse, without our asking any questions on the subject. Some of them name what they have experienced as violence, others don’t: their path to conscientization varies. Mothers describe devaluation, in particular criticism of their mothering skills, but also threats, control, isolation and deprivation of resources on the part of their ex-partner. Half of them mention physical and/or sexual abuse. The accusation of being alienating is in fact one of the ways in which their maternal capacities are devalued. It is based on the idea that to consider questioning the father’s access to the children, in this case because of his violent behavior, is to be a bad mother. The accusation aims to make them responsible for the impact of violence on children, of which reluctance to see their father is one. In this way, the accusation of parental alienation contributes to their confusion. Children are in fact all co-victims of domestic abuse, but also of psychological abuse and neglect. Two-thirds of them have suffered physical and/or sexual abuse. The violent father seeks to isolate them from their mother, and devalues her in their eyes. They may be used to keep an eye on the mother, and witness acts of violence by the father against the mother when they are handed over to the other parent.

The women are afraid of the abuser, but also of the institutions; they fear that denouncing the violence could ultimately call into question the relationship with their children. The abuser uses the joint exercise of parental authority to control the mother, impose his own educational choices on her, prohibit or control activities and medical and psychological follow-up for the children. Generally speaking, judges re-establish, maintain or extend the rights of the abusive father. They can also remove or restrict the link with the victimized mother, if she is deemed to have an unjustified desire to challenge the link with the father. A third of them lost the children’s custody (one regained it several years later). This can happen for a number of reasons: when complaints are dismissed, when mothers are convicted for failure to present a child, or when allegations of parental alienation are taken up by the judge. Half of the mothers had filed a complaint for domestic abuse or child abuse, and almost all of these had also been dismissed, except for two who had been convicted in connection with domestic abuse: in these cases, the respondents were victims of repeated physical and psychological abuse. Two-thirds of them had had their children placed under an educational assistance measure ordered by the juvenile court judge. Such a measure was ordered for all mothers who filed a complaint.

Allegations of parental alienation can come from a variety of sources: from the father or his family, from professionals or associations supporting him (such as his lawyer or members of fathers’ rights groups), from psychiatric experts, from social workers. The expression “parental alienation” is not necessarily explicitly present. Indeed, in two-thirds of cases, the allegations are implicit: the mother is described as “fusional,” she “tries to turn the children against the father,” she “puts in place a strategy so that the father is rejected” or wants “to keep him away from his children.” When parental alienation is explicitly mentioned, it is rare for the situation to be analysed according to any assessment tool or criteria - even if they are invalid - usually associated with the notion. It is a “label rather than a behavioral description” (Milchman et al., 2020: 344).

- Note de bas de page 17 :

-

The first name has been modified.

Valérie,17 45 at the time of the interview, decided to leave her partner when she received her first hit. During their time together, he devalued her and called her crazy. After the separation, he intimidates their five-year-old daughter, who eventually refuses to see him. Valérie files a complaint about the mistreatment of her daughter, which is dismissed. She is convicted of failure to present a child. An initial family court judgment stated that her refusal to hand over the child to the father “is likely to develop in the child manifestations described by specialists as ‘parental alienation syndrome’, and may place the little girl in great danger.” In a second ruling, the child’s custody is transferred to the father, who argued that it “prevents her from seeing her daughter normally and regularly,” whereas “[the daughter] should have access to both of her parents.” Domestic abuse was never taken into account.

Conclusion

The assumption that everything changes with separation, that violence is a thing of the past, and that a violent man remains good enough to raise children persists (Prigent, 2021). In the interviews conducted, maternal protective strategies against coercive control are interpreted as parental alienation. This is encouraged by a lack of understanding of the extent and mechanisms of violence against women and children, which is reduced to a "parental conflict" maintained by the mother. This results in a lack of protective measures and institutional surveillance or even sanction. If mothers lose custody it is difficult (but not impossible) for them to re-establish a relationship with their children; they are stigmatized. For other women, the recurring threat of being accused of alienating their children encourages them to self-regulate: they are under control. The theory of parental alienation reinforces the norm of compulsory parental bonding, and considers women who do not respect it as deviant. Women are judged on the basis of an assumed condition, rather than on the basis of their behaviors, which must be understood in the context of domestic abuse, coercive control and their resistance to it. This logic is symptomatic of the confusion between the child’s interest or protection and co-parenting - even if this confusion seems to be gradually being challenged (Matteoli & Mattiussi, 2024) - and the concealment of domestic abuse, particularly post-separation (Romito, 2018).

In 2021, CIIVISE, the independent commission on incest and sexual abuse against children, formally opposed the use of the theory of parental alienation in an opinion devoted to “mothers in struggle” (CIIVISE, 2021), which received considerable media exposure. A recent report by the Special Rapporteur on violence against women and girls, its causes and consequences advocates that States legislate to prohibit “the use of parental alienation or related pseudoconcepts in family law cases” (UNSRVAW, 2023: 19). The invocation of parental alienation is seen as an "extension of domestic violence" (UNSRVAW, 2023: 3) after parental separation.

Yet difficulties persist in France. Accusations of parental alienation, both implicit and explicit, have not disappeared from the courts. Promoters of the notion of parental alienation are seizing on research into domestic violence and coercive control, and aiming to have the former considered as part of the latter. The theory of parental alienation thus mutates according to resistance to its use. If promoters present cases of mothers who are alienated, it is most often without contextualizing the reasons why they have lost contact with their children. If research could be carried out to examine this context, it is important to remember that mothers no longer see their children after being labelled alienating.

- Note de bas de page 18 :

-

Parental Alienation International, July 2018, “ICD 11 Includes Parental Alienation.”

- Note de bas de page 19 :

-

In France, at a conference on the notion attended by promoters and detractors alike (Mallevaey, 2021), Paul Bensussan referred to us and other colleagues as “fanatics” and “God's fools,” then indicated on X that we were “not the target” and that it was a “metaphor,” even though our names were explicitly mentioned in one of his slides. https://x.com/PaulBensussan/status/1487050798479687683

The “parental alienation” theory promoters argue that the refusal of international classifications to recognize it is linked to “pressure from activist lobbies” (Bensussan, 2021: 40), without mentioning the pressure exerted by the promoters of the notion’s recognition.18 They accuse the notion’s detractors of “activism” in order to discredit the critics,19 lending them a lack of (unattainable) neutrality even though the theory of parental alienation is above all the pseudo-scientific veneer of a misogynist ideology. Attempts to conceal Richard Gardner’s controversial legacy remind us of these sexist underpinnings and the importance of combating them in order to put an end to attacks on the safety and freedom of abused women and children.